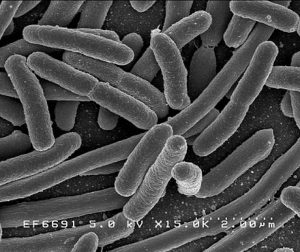

Lawyers often spend their time mulling over unpleasant and murky subjects: murder, violence, taxation etc, but those of us outside of highly specialised legal fields don’t tend to spend much time thinking about microbes. Nevertheless, as the twenty-first century witnesses new threats to human health, particularly in the form of antibiotic resistant bacteria, coupled with new approaches to our environment and our collective wellbeing, microbes look set to become harder for the rest of us to ignore.

We now live in a world where only a minority of citizens remember a time when a scratch from a rose-bush or a winter snuffle could easily, and indeed routinely, take a lethal turn. We are accustomed to basking in the comfortable knowledge that antibiotics can zap into oblivion infections which would once have had fatal or life-changing consequences, and the notion that a previously healthy person might succumb to pneumonia or an ear-infection feels almost medieval. Understandably, it is easy to forget that this was the reality in the very recent past, making the rise of antibiotic resistant bacteria is doubly frightening. We smugly thought that we were safe, and now, vampire-like, the monster has arisen from the grave.

The good news, of course, is that we are not powerless, Transylvanian peasants of Gothic fiction, waiting for the monster to strike when it wills. Contemporary science, both in terms of existing technology and research methods, means that we have an impressive arsenal of weapons with which to fight back, and we can potentially develop new drugs and therapies to combat the new threat. Nevertheless, it would be quite literally suicidal to be complacent, and the choices which we make as a society are likely to decie3 how successful we are in winning the arms-race against pathogens.

This is where law and lawyers come in, as legal systems are what determine the rules we play a part, and not just in terms of Medical Law or counterterrorism. Scientists are now able to give us a more nuanced understanding of the challenges facing us than that enjoyed by previous generations. That said, there are many areas where we are still in the dark, and are only just beginning to see glimmers of light here and there. So, taking into account what we know, and what we suspect, parameters for living and working have to be agreed, and we need to wonder how we restrain individual or commercial choices based on best guesses about collective welfare.

We were intrigued at an event which we recently attended at the Wellcome Trust, to hear one person’s proposition to have a United Nations Declaration on the Preservation and Nurturing of International Microbial Ecosystems. We were attending a talk about humans and microbes out of general interest and curiosity, and hadn’t expected law and the legal solution to feature. Yet on reflection, it is easy, if chilling, to see why mainstream Human Rights, International and Public Law may well be critical in this arena.

Microbes, obviously, do not have passports. They are not minded to stop at national borders, nor adopt a different policy to differing groups of humans. The way in which we behave in this context, from an individual right level, all the way up to the forum of nation States, will have a profound impact upon our neighbours. This means that many factors, including the use of antibiotics in farming and the treatment of farm animals, design of buildings and public spaces, and even the application of antibacterial sprays, bleaches and other cleaning products in homes, may influence how the story plays out. It is also the case that the kind of education which children receive will have an impact on their ability to critically weigh up and assess claims being made by scientists, Governments and politicians.

At the heart of many conflicts and dilemmas in the Human Rights and Public Law field, we have the tension between an individual wishing to assert his or her personal liberty, on the one hand, and the stark reality that sometimes one person’s decision can have profound (possibly lethal) implications for other people. We are already seeing this played out in debates around vaccination, but we may soon see a similar clashes around our approach to microbes and disease. Choices about the kind of food we wish to be able to buy and consume, or the products we want available to clean our homes, may have far reaching consequences.

Certainly, antibiotics in farming have featured in the Brexit debate. Indeed, the United Kingdom’s departure from the EU might leave it free to avoid imposing the ban on dosing healthy animals with antibiotics. This frightening possibility promoted a joint plea from the Royal College of Physicians, the Royal College of Surgeons and the Faculty of Public Health, for the UK to introduce a similar ban, as well as issuing grave warnings about the implications of imported antibiotic ridden meat from the US, and other jurisdictions opposing a large-scale prohibition. Given the magnitude of the effects for us all, it is bewildering that this hasn’t been higher on the public agenda. This is not a matter which we can somehow shrug off and leave to the scientific community. Crucially, in practical terms, the ultimate response has to come from the legal and political system. Anyone doubting why could profitably watch the recent BBC documentary from Michael Mosely: “Pain, Pus and Poison: The Search for Modern Medicines-Pus”. It is a powerful reminder of just how far we have come, and also the kind of place to which most people have zero desire to return.

Related Articles

Pain, Pus and Poison: The Search for Modern Medicines (BBC)

My husband squeezed my hand to say that he wanted to live, then I found a way to save him (BBC News 4/5/19)

Boris Johnson orders action to stop measles spread (BBC News 19/8/19)

UK Medics call for government ban to cut antibiotic resistance (16/11/18)

UK could use Brexit to avoid EU ban on antibiotic overuse in farming (The Guardian 27/9/18)